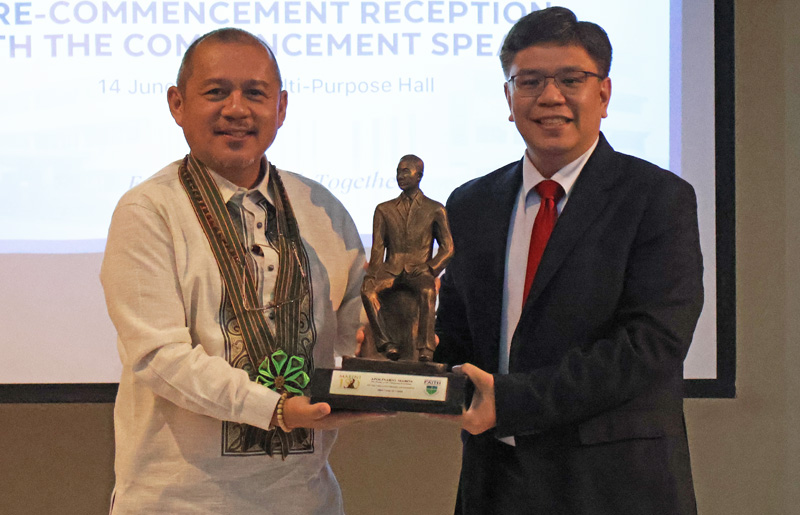

This is the commencement speech delivered by Dr. Clement C. Camposano, Chancellor of the University of the Philippines Visayas, during the graduation ceremonies of FAITH Colleges (First Asia Institute of Technology and Humanities) held on 14 June 2025 at the FAITH Colleges campus in Tanauan City, Batangas. The speech grew out of brief remarks originally presented at the National Conference and Inauguration of the AMIC Office at Philippine Women’s University, Taft Avenue, Manila, on November 25, 2016. It updates and extends the arguments made at that conference by reflecting on key developments in digital media, politics, and citizenship over the last decade.

Dr. Lalaine V. Manalo, Academic and Research, Emmanuel S. Sator, Administration and

Dr. Renelyn B. Salcedo, Student and Alumni Services

In the early days of the internet—that would be the 1990s—there was widespread belief in the promise of digital technology. Early scholarship pointed to “the possibility of entirely new relationships and identities, constituted within new media, and in competition with ostensibly non-mediated, older forms of relationship” 1 (Slater 2002, 533). Indeed, there were those who expected the internet to liberate people from political tyranny. Barlow’s (1996)2 “Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace captured this celebratory outlook, speaking of a world where identities have no bodies and all may enter without privilege or prejudice accorded by race, economic power, military force, or station of birth” (Online).

What I intend to do this afternoon is provide you with a tentative map of the promises and pitfalls of this technology with respect to public life. Let me begin by sharing some ideas I have stumbled upon in the course of an ethnographic study I conducted many years ago. What I attempted to do in that study was describe how Facebook mediates the processes of self-making (a term I prefer instead of “identity formation”), among Ilonggo-speaking male Filipino migrant workers in South Korea. The online lives I followed in the course of my research were both technological and social accomplishments that reveal the complex role of social media in the fashioning of self-identities. Crafted within and through consensual networks, these presentations of selves 3 (Goffman, 1953) raise interesting theoretical and conceptual issues.

Unlike in face-to-face engagements where many of the things we do are realized through our embodied recourse to unstated rules—what Goffman (1983) calls the “Interaction order”—and often in the presence of anonymous others, interactions on Facebook can be more contrived and usually involve people of our own choosing. Through its affordances, Facebook provides low-cost opportunities for self-cultivation, allowing users to engage in more deliberate self-curation. Therein lies its power.

Within the digitally enabled environment of Facebook, users have far greater capacity to present themselves in their own terms. Just as important, recognition and affirmation can also be more easily elicited from an audience made up mainly of one’s own social network (Lorenzana 2016,4 8, see Miller 2011 5 ). Hence, our personal visions of who or what we are, are more likely to be validated on FB than anywhere else.

and Dr. Brian L. Belen, School President, FAITH Colleges

6 Dalsgaard (2008) argues that offline social life is fundamentally different from online sociality. A Facebook person is always at the center of his own social universe, even as he must see his “friends” as similarly situated—i.e., as centers of their own social universes. This is best captured in the oft-used phrase, “walang basagan ng trip” (which I would loosely translate in English as, “to each his own”). Most interactions and engagements on Facebook therefore occur within the framework of this reciprocal relationship that is created when one user admits another into his or her network (McKay 2010) 7. There is a mutuality that is encoded into the very design of Facebook.

In the world of Facebook, we sustain ourselves by receiving and giving affirmation. This may not always happen, but the very architecture of Facebook amplifies this most human of tendencies. This has prompted one eminent sociologist 8 (Bauman 2016, Online) to bewail that what is created through social media sites are networks and not communities. “The difference between a community and a network is that you belong to a community, but a network belongs to you”, he points out.“[It’s] so easy to add or remove friends… that people fail to learn the real social skills, which you need when you go to the street, when you go to your workplace, where you find lots of people who you need to enter into sensible interactions with.”

He argued that social media networks are not conducive to serious dialogue. He laments that, “…most people use social media not to unite, not to open their horizons wider, but on the contrary, to cut themselves a comfort zone where the only sounds they hear are the echoes of their own voice, where the only things they see are the reflections of their own face.” He ends by saying that, “[social] media are very useful, they provide pleasure, but they are a trap.”

This helps to explain how offline friends of many years can end up un-following, un-friending, and even blocking each other on Facebook, and often over issues that, offline, would not even occasion a sharp exchange, let alone a breaking of ties. At the heart of the matter is not so much our capacity for unpleasantness online as it is the nature of Facebook engagements. FB “friends” are people who are supposed to have bought into each other’s self-presentations. A sustained disagreement in one’s newsfeed, whether direct or oblique, can undermine this central assumption of online sociality.

It is easy to imagine how this might have serious implications not only for public discourse but also, and more fundamentally, for citizenship and civic education. Will social media technology—for instance, Facebook in its current form—enable us to mentally (and indeed, habitually) situate ourselves within a larger society beyond friends and family? If a compelling sense of this larger society is lacking in our politics—hence, the personalism and other dysfunctions we regularly witness—can social media be used to remedy it? Put another way, can the affordances of social media be harnessed to create genuine communities, rather than networks?

I remain hopeful about the future, although it is important to point out that the current architecture of social media sites like Facebook could work against this kind of engagement. Which do not mean that they cannot occur, since there are social media forums that facilitate discussion of public issues. Also, we cannot generalize too much across platforms: While Facebook is restricted, Twitter is essentially open. Additionally, Facebook is reciprocal while Twitter tends to be unidirectional. A platform like Facebook can also be many things to many people, and we need to pay attention to the specific ways it is used and/or appropriated by users.

We also need to be more attentive to other kinds of social interaction that occur online. Caliandro (2018) 9 has argued that “the more the Internet expands… the more the social interactions unfolding across it become more ephemeral and disperse.” He illustrates this by describing our use of social media: “[This] very often consists of updating our Facebook status or linking some content posted by a friend, retweeting interesting news, or looking in a particular forum in order to seek technical advice regarding fixing our antivirus software, or maybe posting a comment of gratitude, and then never going back.” 10 Kozinets (2015), for his part, has insisted that we should not underestimate the fluidity of social life in the age of the internet:

Dr. Clement Camposano, 11th Chancelor, University of the Philippines-Visayas

When studying online interactions, we surely wish to identify clear cultural categories such as nationalities, ethnicities, localisms, religiosities, and occupational identities. However, we must strive to view them less as solid states of being than as liquid interactional elements that individual members bring to life.

One may think that, currently, online social life can be either too fragmented or too fluid, or both to promise anything. This looks very challenging, indeed. I should hasten to add, however, that we should not overstate the problem, nor think of ourselves as helpless in the face of these technologies. The situation itself is not static and we need to ground ourselves on evidence, not theoretical speculation. If social media is to effectively serve the ends of meaningful public discourse and citizenship, it needs to evolve further, even as we also need to evolve with it [Is this not, in fact, is the very story of human innovation and civilization? A good example would be our mobile phones which are, for all intents and purposes, no longer just phones].

One way for this to happen is for us to constantly explore ways for social media to be harnessed to offline civic purposes. The fact is, offline is where we bear the consequences of a badly run government, or enjoy the benefits of strong communities. Offline is where we live, and offline is also where we are more likely to become better citizens.

The challenges are very real, but so are the possibilities. Still, we need to get past the challenges and, as a society, confront our fear of digital technology [we need to go beyond the fear of technology going amok, a fear due perhaps to our having watched too many dystopian movies like Terminator, The Matrix, and more recently, Black Mirror]. In historical terms, the Internet is quite young, and digital social media more so. Digital technology will continue to shape us, but so will our continuous engagement with this technology force it to evolve. This relationship is not a one-way process.

Technology and people are co-determining, co-constructive agents, building and shaping each other. I have given the example of our mobile phones. Another very illustrative example would be the way the organization of cities reflect society’s choice of mobility—Los Angeles is obviously organized around cars, and Tokyo, around trains. The more conscious we are of this mutual shaping, the more productive and meaningful our relationship will be with technology. In a pathbreaking study of the social lives of networked teens, Boyd (2014)11 has warned against taking a deterministic stance by arguing that, “[the] context of a particular site is not determined by the technical features of that site but, rather, by the interplay between teens and the site.” What matters is not the site per se but the context that is created by those using it:

As teens move between different social environments—and interact with different groups of friends, interest groups, and classmates—they maneuver between different contexts that they have collectively built… Although navigating distinct social contexts is not new, technology makes it easy for young people to move quickly between different social settings, creating the impression that they are present in multiple places simultaneously.

While online platforms may have greatly extended the potential for plural and even discordant identities, going online, as 12 Miller (2013) asserts, “is now as integral to everyday communication and self-representation as is the telephone or television, and we should abandon the idea of a separated out ‘virtual’ domain.” Cyberspace is not another world. It is part of everyday life. Learning to inhabit this multifaceted reality will likely lead to the new cultural forms—possibly new forms of engagement through the affordances of social media that enhance and expand democratic life, as we for instance create the spaces for new voices to emerge.

Today, aside from the overtly political groups (many of which are dubious), there are groups that advocate animal rights and welfare, pages and sites that promote anything from Philippine native trees to good parking habits. These have proliferated on Facebook. They may not be explicitly political but they show real promise in that they defy the supposedly self-centered and narrowly reciprocal logic of this social media platform. I do not think that Mr. Zuckerberg had actually anticipated what FB would become.

Very likely these forms of engagement will involve multiple digital platforms and the kinds of meaning-making they enable and engender. Miller (2013) and 13 Madianou (2015) label this “polymedia” and it involves users navigating multiple evolving platforms in light of their communicative needs. What the composite structure that emerges from this will eventually look like will depend on how users exploit the affordances of the various platforms available to them. A key feature of this new environment is that users will certainly have more control over how they communicate.

The empirical evidence, so far, is encouraging. Notwithstanding earlier research that suggest online interactions have the potential to undermine civic engagement owing to their tendency to supplant and consequently diminish offline social interactions, recent studies have shown that the size of social networks built via social media platforms is positively associated with young people’s civic engagement with respect to political organizations and non-political charitable organizations 14 (Lee 2022, online). The study also found differences in civic engagement implications between Facebook’s reciprocal connections and Twitter’s more diverse and loosely linked unidirectional ties:

Commencement Speaker Dr. Clement Camposano

The comparison of marginal effects for participation in political groups and participation in non-political charitable groups in Twitter models suggests that the number of social ties on Twitter, in both terms of “follower” and “following”, is a better predictor of civic participation via political organizations than participation via non-political charitable organizations. Facebook social capital [i.e., the quantity of social connections], on the other hand, is a better predictor of participation via non-political charitable organizations (online).

The study cited above suggests that current fears about the dysfunctional effects of social media may well be unfounded or overblown, although there is clearly a need for more evidence. It concludes that, “[despite] the criticisms about young people’s use of social media and the increasing concerns that the changing ways of social interactions contribute to the younger generation’s narcissism and social isolation, the findings reveal the potential of virtual social ties in boosting young people’s civic engagement and prosocial behavior” (online).

Indeed, the author goes a step further to suggest that social media could “provide new possibilities for bottom-up and self-organizing participation for bypassing traditional mass media whose gatekeepers can control the one-way communication” (online). Is this therefore the dawn of a new digital citizenship? Will this rescue us from the mindlessness of vloggers that daily assault our screens? Is this the antidote to the weaponization of the internet by those in power? Or, better yet, the fulfillment of Barlow’s dream?

Whatever the case, I pin my hopes on the digital natives who are right here before me! [Incidentally, I always emphasize that there three basic types of people online, the digital natives, the digital migrant, and the digital refugees—those who never wanted part of this but who were displaced into online spaces]

The idea is to unlearn our anxieties with respect to digital technology and look beyond the pitfalls to embrace the promises and possibilities, and in the process enter into a more meaningful, more productive relationship with it. But what about the threat of AI? What about the possibility of artificial intelligence taking over civilization? Are we not burying our head in the sand, ignoring the existential threat of machines someday going rogue? Allow me to address this vexing subject…

First of all, historically, all great technological innovations have been disruptive, some more than others. All major technological innovations have created problems and some, like that internal combustion engine powering our cars, are even slow-cooking the very planet we live in. AI is just another case of great technology that threatens to reorganize everyday life. Like the internal combustion engine, we will find ways to deal with at some point. Indeed, if a piece of technology is not disruptive, then perhaps it is not so great! There is nothing like an understanding of the broad march of human civilization to teach us that this is but a phase—a phase in our psychological and cultural evolution as a species which Polo calls “humanization”, which he contrasts with our biological evolution or “hominization” (Polo 2016, 9-23)15. But let us not get ahead of the argument. First, allow me to dwell on the question of what AI is and what it is not.

Artificial intelligence are of course computer systems that mimic aspects of human intelligence that include 1.) learning from data, experience, and environments; 2.) making decisions, solving problems, and drawing conclusions; 3.) interpreting and understanding data from sensors, images, or other sources; and 4.) comprehending and generating human languages. At the heart of all these are algorithms, sequences of procedures, rules, or instructions used for performing calculations and processing data [Note: I have Meta AI and Wikipedia to thank for these convenient definitions].

The blinding speed at which AI can perform these tasks is the basis of their power. However, it is their seeming ability to mimic aspects of human intelligence that truly scares many people since they can outperform us humans in a number of tasks, and thus possibly displace and dominate us in the near future. This kind of anxiety has been amplified in recent controversies surrounding AI-generated deepfake videos, and such cases as ChatGPT using Studio Ghibli aesthetics to generate images.

A good number of those who work on AI, however, do not think that continuous development along this line will eventually make AI sentient, that is, self-aware and possessing something that amounts to a consciousness, which is really what explains why humans can have independent motives. The capacity to trawl the web for data and process them, recognize patterns, and autonomously curate information, even if done at mind-boggling speed, will not make AI think like humans.

Experts at the University of Michigan are of the view that claims that AI can soon threaten human civilization are overblown. Among them, Prof. Hafiz Malik asserts that while AI may be able to beat the best human player at chess or diagnose or detect illnesses that doctors cannot, these are “very task-specific things with strict constraints” 16 (Quoted in Blouin 2023, online). Machines, no matter how powerful, do not yet have the capability for “artificial general intelligence” (AGI) which will allow them to “adapt to an almost infinite array of new tasks without being specifically trained or programmed to do those task” (Blouin 2023, online).

Malik and his colleagues also point out that while task-specific AI is now everywhere, AGI does not exist yet and whether it is at all possible is not certain (Blouin 2023, online). A recent study by Apple with a main title, “The Illusion of Thinking”, confirmed this when it concluded that today’s “thinking” AIs such as DeepSeek and OpenAI “produce outputs consistent with pattern-matching from training data when faced with novel problems requiring systematic thinking.” Using puzzle-based experiments, the study revealed that the simulated logical reasoning of current AI models led to “severe performance degradation on problems requiring extended systematic reasoning” 17 (Edwards 2025, online).

The real threat is not with AI displacing human beings, but the role that it plays in powering disinformation and political polarization. This happens because AI are being harnessed to mobilize opinion through the creation of “echo chambers where people end up with very distorted view of reality” (Malik, quoted in Blouin 2023, online). The other problem with AI is “the fact that the highest levels of artificial intelligence are basically controlled by a handful of very large, powerful companies which are developing the technology for commercial purposes, not to benefit human society” (Blouin 2023, online). Needless to say, this situation can lead to the perpetuation of existing systems of inequality.

These are of course not problems of technology. These are problems of politics, of the political economy, and of citizenship. If there is anything that will save democracy and secure and extend the margins of human freedom in the digital age, it is digital citizenship. But this requires that we embrace this technology and not shun it. This is too important, too powerful, to be left in the hands of mindless vloggers and tiktokers, as well as political leaders and commercial interests. We need to harness this technology to generate an expanded and expanding sense of the common good, one that goes beyond the narrow confines of nation-states to address planetary concerns. This can be done because, in fact, it is being done! To borrow a phrase from St. Jose Maria Escriva, efforts are underway to “drown evil with an abundance of good.”

There is a crucial insight I would like to leave you with: I believe our fear of this technology is rooted ultimately not in its raw power, but in our inability to plumb the depths of human experience. Because so many of us are not so sure about what it is that truly makes us human, we fear being replaced by machines, especially when they start to mimic us. We are afraid of AI’s human-like abilities because we are not confidently human, and are thus unsure about our place in a digitally driven future.

To alleviate this diffidence, we need the depictions and explorations of the arts, of literature, of the humanities broadly construed. We need philosophy!

Picasso’s Guernica brings us face-to-face with the violence and chaos of war. Frankl’s autoethnographic account of the holocaust takes us to the nadir of human suffering even as it is also redemptive. The Ilonggo writer Deriada’s Dog Eaters tells us how ordinary lives can become staging points for an extraordinary descent into cruelty and madness. These explorations allow us to embrace our human frailties, even as they ground us in the limits, the dangers, and the possibilities of our embodied existence. This is self-knowledge that teaches us to be confidently human, able to enter into meaningful relationships with the beautiful machines we create.

And then there is the Spanish philosopher Leonardo Polo whose notion of the “technological biology” of man teaches us to think of technology as essential to our evolution as a species. Polo holds that human beings are the only species not adapted to any particular environment. Instead, we possess physiological features that allow us to use tools— technology—so that we can transcend our biological limitations and adapt the environment to our needs. Technology then is not separate from human beings, but rather the very means by which human beings perfect themselves.

Dear friends: Technology is not our enemy. We are our own enemy. Technology is a means to our humanization, a means to fulfill our true nature.

Thank you and again, a pleasant afternoon to all.

Bibliography

1 Slater, Don. 2002. “Social Relationships and Identity Online and Offline.” In Handbook of New

Media: Social Shaping and Consequences of ICTs, edited by Leah Lievrouw and Sonia

Livingstone, 533-46. London, UK: Sage Publications LTD.

2 Barlow, John Perry. 1996. “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace.” Electronic

Frontier Foundation, February 8. Accessed June 12, 2025. https://www.eff.org/cyberspace-

independence

3 Goffman, Irving. 1956. The presentation of self in everyday life. Edinburgh: University of

Edinburgh Social Science Research Centre.

4 Lorenzana, Jozon. 2016. “Mediated recognition: The role of Facebook in identity and social

formations of Filipino transnationals in Indian cities.” New Media and Society, June 27, 2016.

Doi:10.1177/1461444816655613

5 Miller, Daniel. 2011. Tales from Facebook. Cambridge: Polity Press.

6 Dalsgaard, Steffen. 2008. “Facework on Facebook.” Anthropology Today 24 (6): 8-12.

7 McKay, Deirdre. 2010. On the face of Facebook: Historical images and personhood in Filipino

social networking.” History and Anthropology 21 (4): 479-498.

8 Bauman, Zygmunt. 2016. “Social media are a trap.” Interview by Ricardo de Querol. Accessed

January 30, 2016. https://elpais.com/elpais/2016/01/19/inenglish/1453208692_424660.html

9 Caliandro, Alessandro. 2018. “Digital Methods for Ethnography: Analytical Concepts for

Ethnographers Exploring Social Media Environments.” Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 47

(2): 1-28.

10 Kozinets, Robert. 2015. Netnography: Redefined. 2 nd Edition. London, UK: Sage Publications Ltd.

11 Boyd, Danah. 2014. It’s complicated: The social lives of networked teens. London: Yale

University Press.

12 Miller, Daniel. 2013. “Future identities: Changing identities in the UK – the next 10 years, DR2:

What is the relationship between identities that people construct, express and consume online

and those offline?” Gov.uk. Accessed January 22, 2016.

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/275750/13-

504-relationship-between-identities-online-and-offline.pdf

13 Madianou, Mirca. 2015. “Polymedia and Ethnography: Understanding the Social in Social

Media.” Social Media + Society, 1-3.

14 Lee, Young-joo. 2022. “Social media capital and civic engagement: Does type of connection

matter?.” Int Rev Public Nonprofit Mark 19(1):167–89. doi: 10.1007/s12208-021-00300-8. Epub

2021 Jul 2. PMCID: PMC8249427.

15 Polo, Leonardo. 2016. “On the Origin of Man: Hominization and Humanization”, translated by

Roderrick Esclanda and Alberto I. Vargas. Journal of Polian Studies (3): 9-23.

16 Blouin, Lou. 2023. “Is AI really a threat to human civilization?”. University of Michigan-

Dearborn. Accessed June 12, 2025. https://umdearborn.edu/news/ai-really-threat-human-

civilization?

17 Edwards, Benj. 2025. “New Apple study challenges whether AI models truly “reason” through

problems”. Ars Technica. Accessed June 12, 2025. https://arstechnica.com/ai/2025/06/new-

apple-study-challenges-whether-ai-models-truly-reason-through-problems/

Ellison, Nicole. 2013. “Future identities: Changing identities in the UK – the next 10 years, DR3:

Social media and identity.” Gov.uk. Accessed January 22, 2016.

https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/275752/13-

505-social-media-and-identity.pdf

_. 1983. “The interaction order.” American Sociological Review 48 (1): 1-17.